King's Heath Local History Society

The early history of King’s Heath by Ivor Davies

Little is known of the area before the late 18th century. A few earlier references mention land adjacent to it but tell us nothing about King’s Heath itself. However, in the 18th century, it would certainly still have been entirely rural and sparsely populated, with a number of farms and the dwellings, probably mostly isolated, of those who worked on the land. A large expanse of common and heath stretched across the later High Street and Alcester Road South. There was no village or hamlet.

After the Norman Conquest, King’s Norton, Moseley and King’s Heath were all in the Royal Manor and parish of Bromsgrove hence the name, the King’s Heath. By the 13th century, King’s Norton had become a separate Royal Manor and a virtually independent parish, although owing nominal allegiance to Bromsgrove Church. Only in 1846 was the link finally severed

In 1564 Queen Elizabeth sold the manor of Bromsgrove but kept King’s Norton as a Royal Manor and parish, which included King’s Heath as part of the Moseley Yield, one of four divisions for tax purposes. Moseley was a village long before King’s Heath began to grow but there has always been a close relationship between them, so that, even today, it is difficult to say where one ends and the other begins.

King’s Heath is between 3 and 4 miles from Birmingham and this proximity ultimately decided its long term future. More immediately, it was one of the causes of its growth from the late 18th century onwards.

A track-way ran across the heath which gave Worcestershire farmers access to Birmingham markets. It was said that 80 packhorses daily carried produce from Evesham to Birmingham in the 18th century and cattle and sheep would also have been driven along the road. Birmingham’s population began to rise in the second half of the century resulting in an increased demand for food. This would have brought more traffic across the heath.

It would have been hard going on the road, particularly in winter, as there was probably little maintenance carried out. Manors had gradually lost their authority, so in 1555 Queen Mary established the parish as the unit of local government. The church vestry was to be responsible for certain secular duties, one of which was the upkeep of the parochial roads. This depended on forced, unpaid labour, so the task was unlikely to have been done well on a regular basis.

Already, during the ‘turnpike mania’ (1751-72), which finally created a dense network of turnpike roads, an Act of Parliament of 1767 had put the road from Spernal Ash to Digbeth, via the King’s Heath, in the care of a turnpike trust to maintain and to improve it. The cost was met by charging tolls to traffic and gates were set up at intervals for this purpose. It is doubtful if turnpiking the road had more than a marginal effect on the increase in traffic, though it did eventually make the journey easier. The main cause, however, was Birmingham’s burgeoning population, which expanded enormously in the next one hundred years, from about 70,000 in 1801 to 522,000 in 1901.

Improvement to the road seems to have been slow. In 1781 it was criticised as being too narrow and it was only some time in the early 19th century that it was straightened and the surface made more durable. By 1840 it was said to be ‘improving’.

The increasing traffic helped to promote development along the road on both sides of the present High Street. The first inn, the Cross Guns, dates from the late 18th century. It was made by converting two cottages, in 1792 according to a sign displayed on the front of the building. A pear tree growing outside predated the conversion and gave the pub its local name. A much bigger building replaced it in 1897. The Hare and Hounds followed between 1824 and 1828, while the King’s Arms at Alcester Lanes End was formed by joining a cottage and a shop by 1795.

There is no definite record of what other services were available before 1841 but it is reasonable to assume that there would have been a smithy early on and, perhaps, a wheelwright. Thomas Adams, wheelwright, is recorded in King’s Heath in 1802. There may also have been a few shops, particularly in view of an event which took place a few years after the road was turnpiked.

In 1772, an Act was passed for dividing and inclosing the Commons and Waste Lands within the Manor and Parish of King’s Norton in the County of Worcester. The award of 1774 benefited the larger landowners most and resulted in the formation of a number of fairly big estates on which substantial houses were later built, probably in the 1790-1820 period. Additional farm land was also brought into use.

The changes – namely, the growth of Birmingham, improvements to the road and the enclosures – must have led to an increase in jobs in the area – for example, servants and estate workers for the big houses – and a demand for facilities to satisfy the needs of the increasing population.

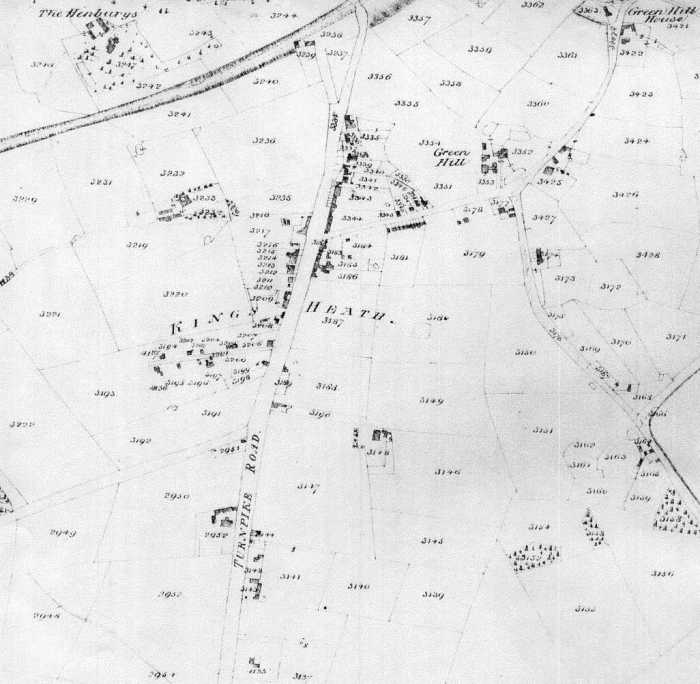

Unfortunately, no plan of the 1774 awards is extant and the first firm record we have of the physical development of King’s Heath is the map of 1840 made in connection with the 1836 Tithe Commutation Act, which abolished tithes in kind and substituted a money payment.

This map shows the presence of a small village along the present High Street and some buildings on two side roads – Silver Street and Poplar Road. There was a farm (Church Farm) on the turnpike road, on what is now the Sainsbury’s site, with a few cottages opposite. A number of big houses are also shown, two of them, the Grange and Kingsfield, adjacent to the road, with driveways leading on to it. There is little else before Alcester Lanes End and King’s Heath is still a predominantly rural community.

However, the map shows another feature which gave a further impetus to growth. In 1840, the Birmingham and Gloucester Railway passed through King’s Heath and a station – called Moseley until 1867 – was opened there. Birmingham was now less than half-an-hour’s train ride away and this easy access to the town helped to promote the more rapid expansion of King’s Heath in the second half of the 19th Century.

It is easy to trace the changes on the ground in the next 40 years or so if we compare the 1840 map with the First Edition 25 inch Ordnance Survey Map of 1884. Most of the High Street is now built up, together with Silver Street and Poplar Road. There are new roads – Valentine, Middleton and Albert. Development has begun to move out from the High Street with house building on Vicarage and Avenue Roads and along the turnpike road beyond Wheelers Lane towards Alcester Lanes End.

It is easy to see the physical growth of King’s Heath from the map but it is harder to appreciate the changes in life style which went with the expansion on the ground. Most people who lived in the King’s Heath of 1840 were still engaged in agriculture or small handicrafts, or were providing for the basic needs of those who were. By 1884, this was no longer true.

Fortunately, some record of the changes is provided in the trade directories which become available at this time. Bentley’s History, Gazetteer, Directory and Statistics of Worcestershire in 1841 give the first mention of King’s Heath in its King’s Norton section. It lists some of the local inhabitants with their occupations.

Between them, they cover a range of basic necessities of a small community which is beginning to grow. There are two grocers and a baker; two boot and shoe makers; a blacksmith and a mason; a grocer/farmer/butcher and a farmer/cooper; two beer sellers and three victuallers; a fire iron maker; a police officer and a railway official; a rope spinner and a manufacturing chemist, who must surely have plied their trades elsewhere, and a number of farmers.

During the next 40 years or so, services increase greatly in both numbers and variety. A count of entries in the commercial sections of directories gives some indication of the speed of change. The 1854 Post Office Directory has only 18 entries in a separate King’s Heath list, farmers still being included in King’s Norton. In 1856 there are 39; in 1868 – 46; in 1871 – 61; the 1880 (now Kelly’s) directory gives 88; while 1884 has 112 entries.

Besides giving the number and variety of services, directories also tell us approximately when they first became available. A chemist, for example, is listed in 1867 and a doctor in 1883. Earlier entries show provision chiefly for every day needs like food and clothing but the later ones point to a changing life style. In 1868, 2 haberdashers, a dressmaker and a tailor are included; in 1871 a newsagent; in 1876 a laundry; in 1878, a bookseller; 1882 has two gas fitters and a piano tuner, while in 1884 there are a house decorator, sewing machine agent and two coffee houses. Surprisingly, perhaps, a sub-post office first appears as early as 1858.

As previously noted, Birmingham was growing rapidly in the 19th Century and great pressure on housing led to expansion into the countryside. During its growth, King’s Heath managed to avoid the worst aspects of Birmingham’s own – the squalid back-to-backs, defective sanitation and polluted water. It came to be known as a healthy spot in which to live and, even before being formally annexed to the City was by the end of the century, well on the way to becoming a dormitory suburb where people could live and travel into town to work.

It developed uniform rows of terraces with larger houses for the better off. In 1871, there were 410 houses and a population of nearly 2,000. By 1891, both figures had more than doubled to 940 and 4,610. In 1901, the population was 10,078.

During the last decade of the 19th Century, estates at each end of the High Street were taken over for housing. Addison, Drayton and Goldsmith Roads were built on land from the Alcester Road Estate (Kingsfield) in 1890, while at the bottom of King’s Heath, the Birmingham Freehold Land Society purchased the Grange Estate in 1895 and seven new roads were laid out. As farming decreased in importance, the inhabitants became a mixture of business, industrial and professional middle class, together with artisans, many of whom worked in Birmingham.

Meanwhile, necessary changes had taken place to fit King’s Heath for its new role. Various institutions suitable to a town or, as it turned out, a suburb were in place by 1900. Pubs have already been mentioned and, in the 19th Century, churches were also established. The Baptists were first with a church in 1815, rebuilt in 1872 and 1898, on its present site in the High Street. All Saints Church followed in 1860 and was given its own parish in 1863, while in 1887 a Methodist Church was erected in Cambridge Road. There was also a corrugated iron Catholic Church in Station Road in 1896.

Law and order was not neglected either. The first police station was on the corner of the future York Road, next to the Hare and Hounds, in the 1820s and later moved to Balaclava Road in the 1850s. From 1852, the Magistrates’ Court sat in a room upstairs at the Cross Guns. In 1893, a new police station and court house were built on a site near the railway.

There was a brewery, dating from 1831, behind the Cross Guns, where the licensees brewed their own beer, but it barely outlasted the century before being sold off to Birmingham Breweries and closed.

After the 1870 Education Act, local boards were set up to build and run state schools in areas without adequate voluntary provision. The first such school in King’s Heath was erected in 1878 at the corner of the future Institute Road. This was not the first such school in King’s Heath, however. A schoolroom, connected with Moseley Church School, had been located at the site of the later All Saints Church in 1856 but closed for lack of finance in 1876.

On the corner opposite the Board School, the King’s Heath and Moseley Institute was opened in 1879. This was a middle-class venture in entertainment and education. The Institute arranged lectures, plays and musical shows. Evening classes were held at a small private school opened to prepare fee paying pupils for grammar school. It had a library, reading room, coffee room and gym. A workingmen’s club occupied the basement. There were facilities for private parties, dances and meetings of local organisations, of which there were a considerable number at this time.

A horse omnibus from Birmingham to King’s Heath was operating in 1851 but services were infrequent and interrupted. Although buses were still certainly running to Alcester Lanes End as late as 1885, the advent of the trams probably killed them off. A steam tram service to and from town began in 1887. The route terminated at All Saints Church and there was a depot in Silver Street. A short distance further along that street a volunteer fire brigade started in 1886. Whilst on the high Street the London and Midland Bank opened an imposing building in 1898.

As most of the changes already described were in or around the High Street, it is surprising that it is not quite clear when the name was officially adopted for that part of the Alcester Road between Queensbridge and Vicarage Road. It first appears in the Kelly’s 1888 directory for a single entry. By 1895 it is in general use in the listings. However, it was probably current locally well before the first date. Previous directories assigned relevant entries to Alcester Road. South was added to the latter in the early 1920s to distinguish it from Moseley’s road of the same name.

Other changes beyond King’s Heath’s control ultimately settled its future. A Local Government Act of 1894 created civil parishes with elected councils, King’s Norton became a Rural District Council, of which King’s Heath was a ward returning two councillors.

Just four years later the civil parishes of King’s Norton, Northfield and Beoley were amalgamated as the King’s Norton and Northfield Urban District Council with greater powers than the parish councils. By this time, Moseley and King’s Heath were the most populous part of the new authority and there was some local agitation for independence, but to no avail. Little more than a decade later, the Urban District was absorbed by Birmingham.

Tithe map 0f 1840 showing King’s Heath